Facebook Juggernaut

By Steven Johnson | 05.16.12 12:59 PM

Sometime in early 2004, as Mark Zuckerberg was furiously coding the first iterations of The Facebook in his Harvard dorm room, the Internet passed what then seemed to be an impressive milestone: 750 million people worldwide had become connected. The exact birthdate of the Internet is difficult to pin down, but it’s fair to say that it took at least three decades for the net to reach a population of that size.

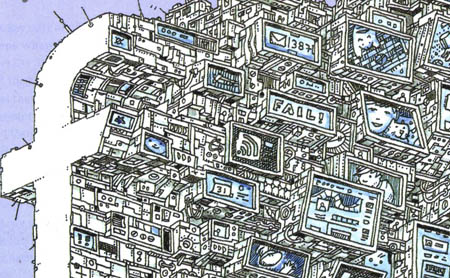

Today, after just eight years in existence, Facebook now has more than 750 million users all by itself. At that astonishing rate of growth, the company is on track to accomplish much more than just a multibillion-dollar IPO. Facebook is on the cusp of becoming a medium unto itself—more akin to television as a whole than a single network, and more like the entire web than just one online destination. The evidence for that transformation goes well beyond the sheer number of users. Many businesses now bypass the traditional web altogether, limiting their online presence to Facebook. Already the platform has spawned one billion-dollar company (the social gaming giant Zynga) and swallowed another (the photo network Instagram). The average time people spend on the site has increased from four and a half hours per month in 2009 to nearly seven hours—more than twice that of any major web competitor.

Facebook’s growing dominance suggests that the platform may very well represent the third major evolution of the network age. First the Internet popularized the crucial organizing principles of peer-to-peer architecture and packet-switched data. Then the web ushered in a new set of governing metaphors that were fundamentally literary in nature: a network of “pages” and footnote-like links. Powerful as they were, though, both those platforms were organized around data, not people. From a computer scientist’s perspective, this might not have seemed like a shortcoming. But most human beings don’t naturally organize the world through metaphors of domains or hypertext; instead they mentally map the world according to their social networks of friends, family, and colleagues.

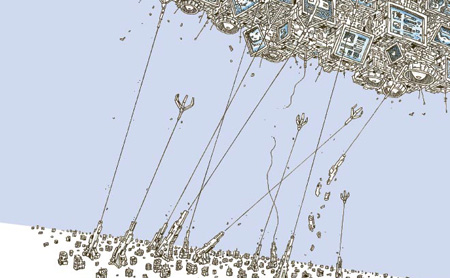

So it should come as no surprise that we now find ourselves gravitating toward a new platform grounded in those social maps. And the bigger we make the platform, the stronger its gravitational pull. The Internet—meaning everything from email to file trading to voice-over-IP phone calls—was always technically larger than the web, but the web’s mass adoption managed somehow to overwhelm the vessel that contained it. The web became the main attraction; the packets and DNS lookups became the plumbing, essential but invisible. Facebook now threatens to perform that same jujitsu against the web itself. The difference, of course, is that no one owns the web—or in some strange way we all own it. But with Facebook we are ultimately just tenant farmers on the land; we make it more productive with our labor, but the ground belongs to someone else.

The sheer magnitude of Facebook’s success is one reason why, as the company charges toward what will likely be the most successful public offering in the history of capitalism, its critics are growing in number. Troublesome corporate behavior is easier to swallow when there are other choices out there, when you have the option to take your business to another store down the street. But when one company owns the whole street, each little transgression is amplified. A few years ago, the primary critique of Facebook revolved around its prodigious capacity for wasting our time. Today the complaints run much deeper: Facebook, we’re told, is a threat to core social values, to privacy, to the web itself.

The most vociferous of Facebook’s detractors contend that it has a long track record of aggressive, if not downright abusive, privacy policies. An early attempt at personalized advertising, Beacon, was famously aborted after users filed a class-action suit claiming that their personal activities online (including purchases made from various ecommerce sites) had been revealed to advertisers and friends without their knowledge. The company’s new Open Graph protocol gives developers the ability to share user behavior in one Facebook app—third-party programs that, like Zynga, run inside Facebook—with other apps that might want the data. For example, if you announce in a recipe app that you’ve cooked a particular dish for dinner, that news can be broadcast to your feed or put to use by a dieting app that tracks how many calories you’ve consumed.

No doubt Open Graph will lead to some wonderfully inventive and useful new tools, not to mention a vast universe of mindless social entertainment. The problem is that most of us don’t have time to monitor all the various ways our actions are going to be shared and tracked across the network. Launch an Open Graph app using your Facebook ID and you’ll get a warning that says something along these lines: “This application may: post status messages, notes, photos, and videos on my behalf; access my data at any time; access my data when I’m not using the application.” Technically, this language is simply describing the consequences of a “seamless sharing” world (in Facebook’s preferred phrase). But as a practical matter, do users know what they’re signing up for?

To Facebook’s credit, the company has given people very granular control over their privacy—the privacy settings page includes dozens of separate options that can be toggled on or off. And it has a long track record of success in putting users at ease, eventually, with new features; initial criticism usually softens into acceptance and, soon, enthusiasm. It’s easy to forget that even the News Feed feature, which now seems unobjectionable (and indispensable), sparked a backlash when it was launched. When the company makes mistakes, it seems to learn from them: Beacon was pulled, and recent updates have greatly simplified the privacy-settings page so users don’t get overwhelmed with the initial dashboard of options.

I suspect that Facebook will forever live within this dialectic, expanding the boundaries of social sharing and then reacting to pushback from users and critics when it goes too far. As long as it continues to listen to those critics, that pattern is probably the best outcome. Given the site’s identity, it makes sense for Facebook to set its defaults such that users share more rather than less; it’s up to the rest of us to help it understand where the limits should be.

When Facebook at long last filed its S-1 statement with the Securities and Exchange Commission in early 2012, announcing its plan to go public, the filing included a letter from Mark Zuckerberg. It was a curious document in the midst of the legalese and financial models: an earnest, plainspoken mix of media theory and hacker mythos. “Facebook was not originally created to be a company,” Zuckerberg wrote. “It was built to accomplish a social mission—to make the world more open and connected.”

A more open and connected world? You’d have to be some kind of cynic or misanthrope to object to such a laudable goal. The problem is that for all his talk of connectedness, Zuckerberg and his company have displayed an increasingly reluctant attitude toward connecting with the rest of the web. The new “seamless sharing” updates make it much harder to follow a link from within Facebook to an outside page. If you see an interesting headline from, say, The Guardian that’s been shared by one of your friends, clicking on the link doesn’t take you to the Guardian website; instead, an “intercept” message pops up, asking you to install the Guardian Facebook app, which will then ensure that all of your favorite Guardian articles flow through Open Graph to your friends. On the tech blog Read Write Web, Marshall Kirkpatrick observed, “There’s something about the way that Facebook’s Seamless Sharing is implemented that violates a fundamental contract between web publishers and their users. When you see a headline posted as news and you click on it, you expect to be taken to the news story referenced in the headline text—not to a page prompting you to install software in your online social network account.” The blogger (and new Wired columnist) Anil Dash, enraged at Facebook’s misleadingly paranoid warnings to users who dare to venture out into the wild web, has gone so far as to suggest that Facebook is essentially malware—and that malware-blocking services should start warning users about Facebook in return.

This reluctance to link to the outside is, to say the least, hard to reconcile with Zuckerberg’s paean to open connection. Hyperlinks are the connective tissue of the online world; breaking them apart with solicitations to download apps may make it easier to share data passively with your friends, but the costs—severing the link itself and steering people away from unlit corners of the web—clearly outweigh the gains. Surely we can figure out a way to share seamlessly without killing off the seamless surfing that has done so much for us over the past two decades.

Beneath all of these critiques lies a more fundamental issue, one that Zuckerberg can’t simply wish away with better privacy policies or user interfaces. We can trust him when he says, in his S-1 letter, that he’s motivated by the desire to extend the web of human connection; he seems like an earnest, well-meaning, and appropriately ambitious young man, and the goal itself is unimpeachable. But ultimately he will have to come to terms with his own success. It’s admirable for him to say that Facebook is more social mission than business, and perhaps he even believes it. But Facebook is more like infrastructure now—like roads and bridges and plumbing, the kind of networks we all rely on.

In the letter, Zuckerberg included this remarkable line: “We think the world’s information infrastructure should resemble the social graph—a network built from the bottom up or peer-to-peer, rather than the monolithic, top-down structure that has existed to date.” If by “to date” Zuckerberg means up until around 1975, then he has an excellent point. But if by “to date” he means, well, to date, then his claim simply doesn’t hold up.

We have had a bottom-up, peer-to-peer network that has served us quite well for several decades now. In fact, we’ve had two: the Internet and the web. To date, the open, nonproprietary networks have always won out over the closed ones, as the dustbin of tech history has filled with walled gardens like CompuServe, Prodigy, and of course the original AOL, which survived only by tearing down most of its walls. For a while it seemed as though social network platforms would follow a slightly different pattern: Instead of a single open platform dominating, there would be a succession of proprietary networks, waxing and waning in micro-generational rhythms: Tribes, Friendster, Myspace. But somehow Facebook reached escape velocity and broke free from that cycle.

The platforms of the web and the Internet are pure peer-to-peer, owned by all of us. Facebook is a single corporation, owned by shareholders, and the social graph that Zuckerberg celebrates is a proprietary technology. We can help Facebook build out its Open Graph by sharing each Spotify track or Guardian article we consume. If we want to opt out, we can delete that data. But we can’t take it with us.

And when we think about ownership, there’s something else to consider: Not only does Facebook own our data, but ownership of Facebook itself is remarkably concentrated. The most startling revelation in the S-1 is not Facebook’s sweepingly ambitious social mission but rather the fact that Zuckerberg personally controls 57 percent of Facebook’s voting stock, giving him a command over the company’s destiny that far outstrips anything Bill Gates ever had. The cognitive dissonance here is remarkable: Facebook says it wants peer-to-peer networks for the world, but within its own walls the company prefers top-down control, centralized in a single leader.

Which brings us to one unexpected force that might bring down Facebook. The S-1 contains 21 pages of text delineating the risk factors facing the company in the coming years, including extensive descriptions of the competitive threats it faces from Google, Twitter, Microsoft, and other social networks abroad. And yet the document is almost entirely silent on the opposite hazard: the risk of no competition, which might bring down the hammer of antitrust. In the S-1 the only oblique reference to that possibility comes in a single bullet point alluding to “changes mandated by legislation, regulatory authorities, or litigation, including settlements and consent decrees, some of which may have a disproportionate effect on us.”

Zuckerberg is on the record happily describing how, when Facebook’s photo service was introduced, it almost instantly became the largest digital photo repository in the world, despite a feature set that was obviously inferior to those of competitors like Flickr and Photobucket. Zuckerberg’s point was that Facebook’s social network is so powerful that the ability to circulate your photos on it trumps anything a rival service could offer. But in an antitrust context, Facebook’s instant dominance in photo sharing looks like something more troubling: a company using its clout in one field to squash competition in another. Assuming its growth continues, the next time Facebook makes an Instagram-scale acquisition, you can bet that lawyers at the Department of Justice will be reviewing it very closely.

Facebook is correct to point out that it has plenty of competitors. Google+, for instance, has accumulated more than 170 million users in less than a year, and there’s no shortage of smaller networks reaching critical mass—Foursquare, Path, Spotify, and others. But Facebook dwarfs them all and continues to expand, swept along by the winner-take-all dynamic of network growth: As more people join a network, the network gets more useful, drawing even more people on board. The last two times we’ve seen runaway network effects on that scale were with the Windows platform in the 1990s and Google’s advertising business in the 2000s—and both Microsoft and Google ended up facing antitrust scrutiny. In its S-1, Facebook seems more worried about being undermined by competition than being perceived as a monopoly. But history suggests that antitrust investigations might prove to be the bigger threat. If Facebook continues its transformation from website to medium, Zuckerberg and his team may well have to figure out a way to move their social network, or at least parts of it, onto an open standard.

It may make Zuckerberg feel better to say that Facebook “wasn’t created to be a company.” But a company it has become, one of the most powerful in the world. Facebook, to its great credit, has made the world a more connected place. But if Zuckerberg wants openness to remain part of its social mission, he’s going to have to start tearing down some walls.